A Savings Account

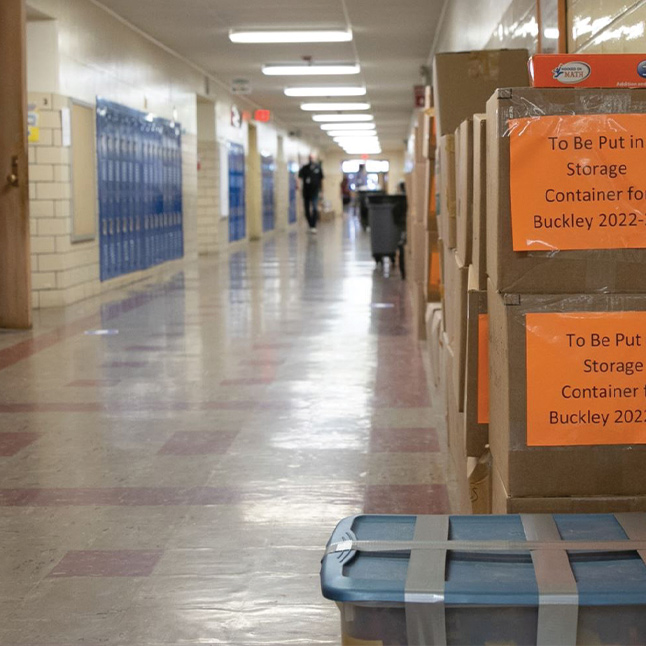

Groundbreaking for the renovation of Buckley Elementary School signals the start of an unprecedented, comprehensive energy efficiency campaign in Manchester.

- Jimm Farrell

On Wednesday, June 2, 2021, under a sunny early evening sky, about 50 people including lots of local dignitaries gathered on the lawn in front of Buckley Elementary School for a groundbreaking ceremony signaling the start of an approximately $28 million renovation project that will make Buckley the first ‘net zero energy’ public school building in the state.

“This is a great day,” Mayor Jay Moran said before adding “and there’s no better way to celebrate than digging some dirt.” And that’s what he and others soon did, donning safety vests and hard hats and grabbing shiny golden shovels to overturn soil from a pre-placed mound.

In 14 months, Buckley will have photovoltaic panels on the roof, a rotating, pedal-fanning ‘solar smart flower’ out front, heating and cooling systems that are tied into geothermal wells, with these and other features ensuring that the total amount of energy used at the site will on an annual basis be equal to the amount of renewable energy created there.

The renovation will take 14 months and concurrently there are other ambitious projects underway in town as Manchester is taking advantage of unprecedented, arguably-best-in-the-country industry incentives to upgrade its building infrastructure by implementing sustainability initiatives, such as energy efficient technologies.

In addition to the Buckley renovation, workers this summer will be at six other schools as well as the Senior Center, Police Station and eight other town buildings. Among many other upgrades, they will be swapping out thousands of lights with highly efficient LED fixtures, capable of being programmed for occupancy/vacancy, task light tuning and daylight harvesting. The lighting overhaul alone is expected to pay for itself in 3-5 years and then reduce lighting costs by 60 percent annually for 20-plus years after that.

Spurred by further efficiency incentives, the town is also upgrading heating, cooling and other systems in municipal buildings — repairing compressed air system leaks, installing high efficiency pumps, variable speed motors, insulation and more, all to use less energy.

And in yet another sustainability initiative, the town is working with partners including Connecticut Green Bank to install photovoltaic panels atop nine buildings (including seven schools) at no cost to the community, but bringing an estimated $3 million in energy savings over 20 years.

“I know of no other community doing things in such a comprehensive way,” Superintendent Matt Geary said during the groundbreaking, referencing not just the current work but an overhaul that will include the renovation of two more Manchester elementary schools to ‘net zero energy’ status in quick succession after Buckley is complete.

Energy and infrastructure are front-page news these days, globally and locally, and Manchester is taking an aggressive approach — investing heavily but, officials believe, smartly — in energy efficiency projects that will have significant benefits for a long time and could serve as a model for sustainability within communities throughout the state and country.

An inner-ring suburban town with almost 60,000 people, Manchester is typical in that it has lots of old municipal buildings. Buckley opened in 1954, part of a post war boom that also included construction of Bowers Elementary in 1950 and Keeney Elementary in 1956 (these being the two schools scheduled to be renovated to ‘net zero’ right after Buckley is finished).

As for work sites this summer, they will include buildings originally constructed as far back as 1913 (Bennet Academy), the Senior Center (1921) and Mary Cheney Library (1937).

Of course, these and other buildings have received energy-efficiency ‘upgrades’ periodically over the years, but it’s always been piecemeal, with the town never having made the kind of comprehensive, immersive, coordinated, consequential commitment to addressing sustainability and energy conservation in infrastructure for both school and municipal buildings as is being done now.

And we are going to cover it all. During the course of the Buckley renovation — over 14 months, from the recent ground-breaking through next year’s ribbon cutting — we will be exploring through periodic installments all elements of the work being done in Manchester by the town and its many partners.

There’s a lot at stake — financially, environmentally, politically and otherwise — and we will dig into each area.

Money? When planning the renovations of Buckley, Bowers and Keeney, town leaders pledged to build in a 5 percent increase to cover costs related to pursuit of net zero energy. That brought the total to $88 million, which voters approved by referendum in 2019. Two-thirds of that is to be reimbursed by the state through its Office of School Construction Grants and Review, and town staff that include Facilities Manager Chris Till are relentless in pursuit of incentives and efficiencies, but in the short term there’s no doubt that it costs more to create net zero energy buildings and efficient systems in general.

But as Mayor Moran said during the groundbreaking, Manchester residents overwhelmingly supported the referendum and the investment it represented.

Clearly, the world climate crisis has brought added urgency to this kind of work. There’s plenty of evidence that rising temperatures are exacerbating weather extremes with fallout that includes economic disruption, food and water insecurity, and more. Manchester is just one town, yes, but experts agree that collective action is needed to reverse trends that are ominous.

At the Buckley groundbreaking, Mayor Moran also bragged that there are more affluent neighboring communities that are surprised Manchester has positioned itself as an environmental leader. He also noted that more former politicians than current office-holders were attending the groundbreaking, a nod to the long journey the town has taken to get to this point — and that’s part of this story, too. A critical milestone in the school renovation evolution came in 1999, when residents rejected a $110 million plan to renovate the then 10 elementary schools serving students in K-5. Three years later voters rejected an even more expensive plan that called for construction of a new high school and upgrades to all other schools.

Dispirited public officials in both cases acknowledged that residents were clearly demanding a more prudent, comprehensive, sustainable approach.

Progress over the two decades since has been slow with the most meaningful work done by two iterations of a committee known as the School Modernization and Reinvestment Team Revisited. More recently, the town created a Sustainability Commission charged with recommending environmental and sustainability actions and investments.

We’ll review the influence that these groups have had on getting where we are today as well as the role of many more people and institutions — engineering firms that have conducted energy audits, architects doing design work, contractors handling construction, power companies offering incentives, and many other players who will emerge in the coming months.

Our reporting will aspire to be explanatory, examining everything from the ABCs of LED lighting to principles of building design to the scheduling challenges inherent in complex, multi-phase projects that will have dozens of companies bringing hundreds of workers to town, often with many under the same roof at the same time.

Through stories, photos and video, we will be documenting the transformation of Manchester buildings because this is a great opportunity for a deep, revealing, instructional dive into the kind of work that is or will soon be happening in communities throughout the state, country and world.

The Manchester Energy Efficiency Project is complicated, sure, but we promise to provide context and clarity and we’re sure you’ll learn a lot as you follow along.

Coming soon in Chapter 2: Just how much energy do schools and other town buildings use, anyway? And how much could be saved with sustainability and energy conservation?