The Tipping Point

Police brutality is a symptom of the larger disease: Systemic racism

The first time I had an honest, productive conversation about racism and the issue of police brutality in the United States was my sophomore year at Manchester High School during an English class. It was a roundtable discussion known by many high school students as a “Socratic Seminar.” This particular conversation was held in response to the 2015 Baltimore protests following the death of Freddie Gray, who was killed while being transported in a police vehicle. However, Freddie Gray was not the first Black person to be killed by police officers, nor has he been the last. Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland. The list goes on. These are just some of the names that were recalled by students during that Socratic seminar. Within the 5 years that have passed since that discussion, the list of names has grown and now the focus has shifted to the death of George Floyd, a Black man who was murdered by white police officers in Minneapolis on May 25. In haunting similarity, Floyd repeated the same words spoken by Eric Garner prior to his death, a statement now being shouted in protests across the nation: “I can’t breathe.” The same desperate plea, but 6 years apart.

Contrary to certain arguments, police brutality against Black persons is not the result of “a few bad apples,” it is a historic, institutional issue and only one example of the systemic racism ingrained in American society. While we are now witnessing protests and visible outrage sparked by the senseless murder of George Floyd, this same outrage has been simmering and ready to boil over for years. The simple truth is that the exasperation and passion demonstrated in these protests is not solely about police brutality. Protestors are revolting against the greater systemic issue in which racism has been ingrained in all major institutions of society. Systemic racism is the disease, and police brutality is but a symptom.

The statistics alone demonstrate clear racial discrimination and inequality in America. According to a 2016 study by Ashley Nellis, Ph. D., “African Americans are incarcerated in state prisons across the country at more than five times the rate of whites, and at least ten times the rate in five states.” The U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection has released data showing that “from kindergarten through high school, Black students are nearly 4 times more likely to be suspended and nearly twice as likely to be expelled as white students.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that Black women are 3-4 times more likely than white women to die from complications relating to pregnancy. In a study published in the American Economic Review, Black patients who saw Black doctors received 34 percent more preventative services, but only 4 percent of physicians in the United States are Black. The COVID-19 pandemic has dragged the racial bias in our healthcare system into the light, as the virus has disproportionately affected people of color. Black people account for 13 percent of the US population, yet they make up 24 percent of US deaths from COVID-19 where race is known. Another shocking statistic is the considerable wealth gap, in which Black Americans own approximately one-tenth of the wealth of white Americans. Keep in mind, these are just a handful of statistics that demonstrate how the institutions in our society, from education to health care, are inherently racist and are set up to fail those of color.

Placing the death of George Floyd and the history of police brutality in the context of institutionalized racism, it is easier to understand the current outrage and protests, occurring not only in Minneapolis, but from coast to coast. The rise of protests in cities across the nation demonstrate how this narrative is consistent across all parts of American society. Even in Manchester this past April, Jose Soto, a 27-year-old Latinx man was shot and killed by four officers from a regional special weapons and tactics team on Oak Street. Soto, who suffered from PTSD, was speaking irrationally about possibly having a weapon but his mother, Noraida Diaz, told officers that he did not have a firearm. The American Civil Liberties Union of Connecticut has questioned why the Department of Correction decided to track down Soto for a parole violation during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, since officials were urging people to stay home. Danisha Soto, Jose Soto’s sister, stated that there was no weapon ever found. “He stepped out quickly, put out his hands to show that he didn’t have a gun, and they shot him down in cold blood,” she said. This is an example, much closer to home, of police killing an unarmed person of color.

It is crucial that we do not allow this visible outrage to once again go silent as another headline overtakes the spotlight. Anti-racism efforts should not be a trend that ebbs and flows with current events. While social media may eventually go silent, racism will continue to affect the lives of people of color on a daily basis. Those who are white, like myself, have the ability to turn a blind eye and forget because we do not have to face racism in our daily lives. People of color do not have this option, instead they continuously endure racism on both micro and macro levels.

In light of this, I encourage all white people to acknowledge our racial privilege and recognize that we benefit from a system of oppression. Peggy McIntosh, author of White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack, describes her realization of this structure: “I was taught to see racism only in individual acts of meanness, not in invisible systems conferring dominance on my group.” McIntosh continues to describe how, “as a white person, [she] realized [she] had been taught about racism as something that puts others at a disadvantage, but [she] had been taught not to see one of its corollary aspects, white privilege, which puts [her] at an advantage.” The word privilege can be misleading because it indicates that the state of advantage was earned or gifted, but privilege in this context means that dominance was granted simply on the basis of race.

Acknowledging and describing white privilege is the first step in holding yourself accountable. Although it may be an uncomfortable process, it is crucial that we then go further after recognizing white privilege. Having this privilege does not mean you are a terrible person and it certainly does not mean that there is nothing you can do to change the system. Next, it is important that we ask ourselves, what steps can we take to dismantle the system of oppression and how can we expand our privilege to include those who lack it? These steps involve understanding what it means to be a white ally to people of color and in the struggle against racism. While being an ally does not mean that you understand what it means to be oppressed on the basis of race, it does mean that you are taking on the struggle as if it were your own. There is a well-known quote that states “justice will not be served until those who are unaffected are as outraged as those who are.” I call on all white Americans and Manchester residents to become just as outraged. Take action and make a commitment to anti-racism. If we allow ourselves to fall into the trap of publishing an aesthetically-pleasing post on social media condemning racism one day and then returning to the bubble of our white privilege the next, then change will only become more difficult to achieve.

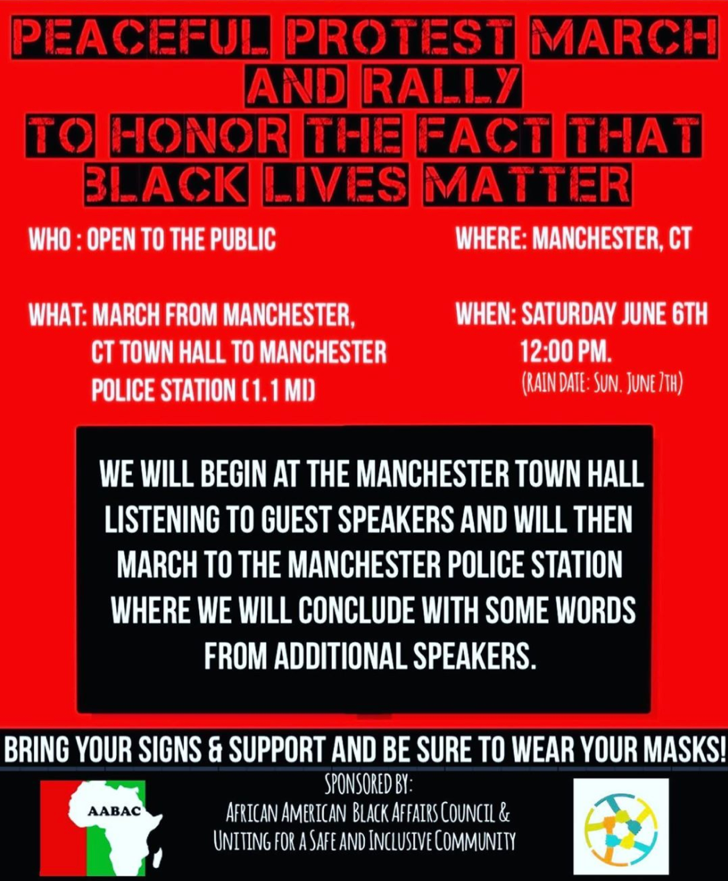

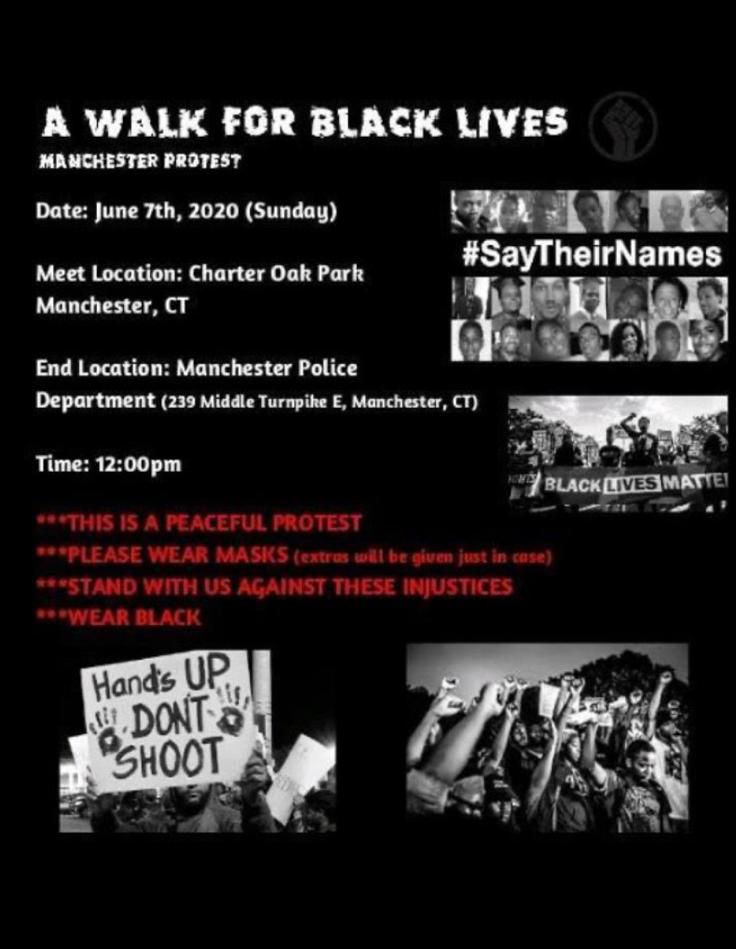

One place to start is right here in Manchester, in our own communities and around our dinner tables. The fact that my first open, academic conversation about racism and police brutality took place in my sophomore year at Manchester High School, at age 15, demonstrates the need for greater education. There are a variety of ways to make a difference in our local community, whether that be increasing education on race, getting involved in activism, donating to activist organizations, signing petitions, or calling legislators. Part of being an ally also means amplifying Black voices and demonstrating solidarity. This includes buying from Black-owned businesses, sharing content made by Black creators, and supporting Black artists. These are just a few tangible actions that can have greater impact when taken by those who hold greater privilege and power. For those who are able to attend, I strongly promote the attendance of the peaceful protests planned for this weekend at the center of town. These local protests are a powerful way to physically show solidarity, hear from community members, and recognize that Black lives matter. Right here in Manchester, there is an opportunity for change to be made and we all have a responsibility to make a stand against injustice.

Additional Resources:

Like this article?

Leave a comment

About Author

I am a lifelong resident of Manchester and a Facility Director with the Department of Leisure, Families, and Recreation. I graduated Manchester High School in 2017 and I’m currently an undergraduate student majoring in International Studies at Boston College. I am an editor for The Gavel, a progressive student publication, and a co-director for FACES, the anti-racism student organization at Boston College.

Fun Fact #1: I studied abroad in Granada, Spain. The Alhambra was the most beautiful place I’d ever been.

Fun Fact #2: I can speak Spanish and one day want to be fluent.