Why Race Matters in Manchester

- Rhonda Philbert, MPH Master of Public Health

Race matters. It matters everywhere and certainly here in Manchester, affecting things that are sometimes obvious (like decisions about what schools we have closed and which ones we are renovating) and often subtle (little slights and biases as people who live and work here interact with one another) and all sorts of things in between.

Race matters in Manchester because we have become, over the last few generations, very diverse. If you are 70 years old and grew up in Manchester, you remember when this town was more than 98 percent white. Today, it’s less than 60 percent white —and in our public schools white students make up just 35 percent of our enrollment.

Race matters in Manchester because many people in town—black, white, mixed and others—are working to acknowledge and address the unfair practices that have impacted people of color in town and the school system. Many people in Manchester —but not all of us—understand that as long as people are complicit in status quo practices that exclude people of color (and other people with marginalized identities) and don’t recognize that their lived experiences matter, injustice will continue.

Of course, some people might disagree with my assertion that race matters. Some people—some white people, that is—say “I don’t see color” and go on to explain that people are just people and that everyone should just be judged and treated the same no matter what.

Sorry, but it isn’t that simple.

I’m a black woman. I’ve lived in Manchester for 25 years and raised two children here. I started teaching here in town in the ‘90s and am now the district’s Equity Coordinator, which means I’m involved in the latest phase of work designed to ensure that all children—and their families—are more successful and feel more accepted than they have been in the past.

And our past isn’t great. In fact, I’m embarrassed that our town has the ugly nickname of Klanchester but I know why we have it, because I’ve seen and experienced racism, sometimes overt, during my years of living here. But I’ve also been encouraged to see the town make some simultaneous gradual progress toward becoming a more inclusive and welcoming community. And I’m encouraged because when things get especially ugly, the town always responds. Sometimes, the response has been to create programs that have included difficult, formalized conversations that, I believe, are crucial if we are going to be a place where people who are different from one another are going to thrive together. But I also know that conversations are not enough, especially if people are not willing to really speak their minds.

That’s what I’m trying to do here. Speak my mind. I’m going to try to answer the question “Why does race matter?” by providing insight into my lived experience as a black woman to hopefully give context to the need for the race and equity work occurring in Manchester Public Schools and the Town of Manchester.

“My parents would not let me invite you because you are black.” I was devastated and questioned if I ever wanted to have white friends again.

Rhonda Philbert Tweet

My Story

When it comes to race, every point of view and opinion is extremely personal. What we feel, what we believe, what we think—it’s all informed by who we are and what we’ve lived.

I am a city girl, born in Brooklyn, the oldest of three daughters. My father was a sharecropper who left North Carolina in the late 1940’s during the Great Migration of African Americans who left the south and moved to the North to escape Jim Crow, discrimination and poverty. My mother and her family are from the Island of Trinidad, located in the West Indies.

We often took trips to North Carolina during the summer to spend time with relatives and I learned that my dad’s great-grandmother was an enslaved woman named Miriam.

Despite the unfortunate atrocity of slavery that occurred in my lineage, I was taught to be proud of who I am.

I grew up during the civil rights era. My father followed Dr. King and often talked about civil rights and justice, and I remember songs with words like “Say it Loud, I’m Black and Proud.” Both of my parents followed Malcolm X.

My parents made sure that my sisters and I knew that black people contributed to America in many ways. They provided us with books and told us stories about well-known African Americans. My mom still has pictures of my dad at the 1963 March on Washington at her house in Brooklyn.

When I was about 6 years old and playing in the sandbox at school, one of my white classmates asked to see the inside of my hands and they looked just like his. But when we flipped our hands over to compare the outside, he said “you are black!” and made a noise like something smelled bad—and it was at that moment that I realized the color of my skin was, to some, a bad thing. I had been taught that my dark complexion was beautiful.

When I was 7, my family moved out of “the projects” and into a house in a predominantly white neighborhood. The existing homeowners were not happy about having black neighbors and the following years were turbulent, with many of our fellow African American homeowners having their property damaged by unhappy white neighbors.

As I got older, there were other incidents.

There was the time a friend told me how excited she was about her upcoming 13th birthday party. A few weeks later, I asked when the party would be held. “We already had it,” my friend said. “My parents would not let me invite you because you are black.” I was devastated and questioned if I ever wanted to have white friends again. When I told my mom what happened she told me “You don’t go to school to make friends, you go to school to learn.” My father tried to console me by saying “there are good and bad people of every race.”

Even when I went off to college—at the University of Hartford—I experienced racism, as I had an adviser who constantly questioned my ability to successfully complete my program. In fact, in my senior year my adviser refused to arrange an internship for me, stating “You will not be a good representative for this university.” Well, I earned my Bachelor’s degree—and went on to get my Master’s of Public Health from Southern Connecticut State University in 2014. Just to be clear, my UHart professor was white, and I believe his feelings about me were rooted in assumptions he made based on my being black.

What brought me to Manchester? After graduating from UHart, I returned to New York and taught in a Brooklyn high school for 10 years, during which time I got married, had two children, and then got divorced. In the early 1990s I moved to Connecticut, taking a job with the city of Hartford Health Department as a maternity outreach educator supervisor. I lived in Vernon for a while but moved to Manchester, because it was more diverse. I thought Manchester would be a better place to raise my children. I’m not sure I was right.

Manchester and Race

When I moved to Manchester, it was apparent that the town struggled with race relations. I became a member of the Manchester Interracial Council and it was during these meetings that I learned about Manchester’s past and struggles with race relations. For example, in the early 1970s the Federal Department of Urban and Housing Development offered tax breaks and housing assistance to towns.

Manchester refused the money because they did not want the federal government involved in their affairs and—I believe—because town leaders did not want more of the kind of affordable housing that would bring more black and brown people to town.

I also heard the stories. In the 1980s, I’m told a white resident threw a torch into the home of a black family. And I was here in 1998, when people told police they saw two teenage girls drag a 10-foot cross into a field along Olcott Street near Spencer Street (which is close to Squire Village) and light it on fire. No arrests were made but it was treated as a hate crime.

I’m sorry to say that the stories were soon to be reinforced and validated by my own personal experiences. I started teaching at Manchester High School in 1996 when approximately 80 percent of the district’s students were white. When I moved to Illing Middle School a year later, I was disappointed to see so many black and brown boys in the halls because educators (who back then, and still today, are mostly white) had thrown them out of class.

In my teaching career in New York, I’d been encouraged to keep children in class because “they couldn’t learn anything in the halls.” I was saddened to see that Manchester didn’t share this philosophy, at least when it came to students of color. I don’t doubt that in some cases a student’s behavior was unacceptable, but I also believe —and there has been research to back this up—that white teachers have been socialized to discipline black and brown children more harshly than their white classmates.

At the time, at that stage in my life and career, I did not speak up, but I am now not afraid to say that I believe many of my teaching colleagues (who were mostly white) didn’t know how to connect with black and brown children and were afraid of or felt threatened by them.

There were other racial disparities as well. In the early 2000s, Manchester was considered to be the most disproportionate district in the state in terms of over identifying black students as intellectually disabled —with black males five times as likely to be identified, compared to white males. It was almost as bad with Hispanic students compared to white students.

Still, in the midst of all this, there were sparks of hope. In the 1990s the Manchester Interrelations Council sponsored a series of Community Conversations about race which culminated in the establishment of a welcome center at Town Hall and the creation of the “Racial Unity for a Better Community” logo for use on town and school stationery. Manchester High School adopted the Community Conversation about Race study circle model for students. And, in 2001, Manchester Public Schools established the Office of Equity Programming, with the charge of eliminating disparities of opportunity and achievement.

In 2007, when I began working full-time at the Office of Equity Programming, I had no way of knowing that the Office would be dismantled just one year later.

"I think Manchester is headed in the right direction. The achievement gap is shrinking. We have increasing numbers of black and brown students in groups like the National Honor Society."

Rhonda Philbert Tweet

At a Board of Education meeting in 2008, my friend and colleague Diane Clare-Kearney, who was the Equity Director, talked about the disconnect between black and brown boys and middle class and white teachers, citing the same sorts of issues I had seen while at Illing. Diane said that black and brown boys learned differently—and she was vilified, with the teachers union saying she was guilty of racial stereotyping and that her comments were “irresponsible and divisive.”

Newspaper articles were written and fallout meetings held and all of the progress made by the school system along the lines of achieving equity for all students came to a screeching halt. The Office of Equity Programming was dismantled and Diane was transferred to another position. I stayed on as the Equity Coordinator, but the district commitment to the work was drastically reduced as were the hours I was permitted to contribute to this work. Some principals in the district told me that they were not ready to have me come into their schools to facilitate training (about equity, race and culture) for their faculty and staff members after the reaction from the teacher’s union and board meeting.

I was devastated. I felt the district really did not care about students affected by injustices that occurred in the school district as a result of systemic racism and that some individuals had prioritized maintaining their power at the expense of children of color.

Where We Are Today

That was how it was. But today the tide is shifting and I see around me cause for hope once again.

Under the current administration, the district has been working to acknowledge Manchester’s racial history—and the disparities that continue to exist—while taking steps toward creating a brighter, and more just, future.

A district administrative workgroup—consisting of Superintendent Matt Geary, Dr. Diane Kearney (now the Director of Adult and Continuing Education), Angella Manhertz, Ann Fuini, Erin Ortega and myself—was formed to explore and address racial equity issues in Manchester Public Schools. This work culminated in a multi-week training for all district administrators, facilitated by local and national experts in the field.

In 2017, with funding from the William Caspar Graustien Memorial Fund and the Nellie Mae Education Foundation, Manchester Public Schools worked with RE-Center to conduct an evaluation of the district’s culture and climate through the lens of racial equity and its intersections. The Equity School Climate Assessment (EISCA) examined the educational, emotional, and social experiences of staff and families from marginalized groups to uncover institutional and systemic inequities that prevent all students from reaping the same social and educational benefits. (See “EISCA Provides Blueprint for Improvement,” page 9.)

Shortly after the school district began its equity work, the town followed suit, contracting KJR Consulting to solicit input from residents through focus groups, individual interviews, and a town wide survey. The recommendations developed from this input were developed into a strategic plan for equity and inclusion and presented to the Board of Directors in July 2019.

"These developments and commitments from the school district are encouraging but they are just the beginning."

Rhonda Philbert Tweet

For more information, see townofmanchester.org.

I think Manchester is headed in the right direction.

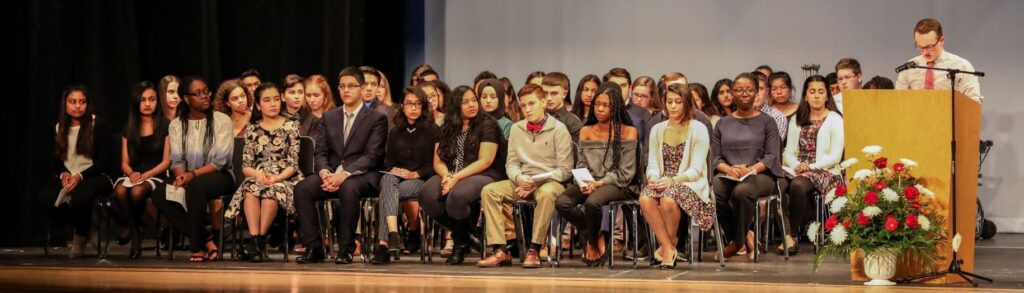

The achievement gap is shrinking. We have increasing numbers of black and brown students in groups like the National Honor Society. We’ve had success with programs like a town-school collaboration to train Emergency Medical Technicians, which has traditionally had trouble attracting minority candidates. (See “Desire for Diversity is Behind EMT Program,” page 11.)

These developments and commitments from the school district are encouraging but they are just the beginning.

As a black woman in Manchester, I know wherever I go I will be confronted with the perceptions, biases (both conscious and subconscious), and stereotypes that our culture teaches about black people. Whether at the grocery store or at the Board of Education meeting (such as the one just after I received tenure where white residents made disparaging comments about the qualifications of non-white educators), I am constantly reminded of the prejudices associated with the color of my skin.

And I’m not the only one.

A colleague of mine, a black man who lives in town, told me he has been pulled over by the police repeatedly in Manchester, for what he believes is mostly because of the color of his skin. This is an indication of how people of color are vulnerable to the injustices that impact their lived experiences.

But hopefully things will improve. Every three years, Manchester Police officers participate in Fair and Impartial Policing training, which includes discussions about cultural competence. The police also continue to emphasize community policing and provide School Resource Officers in order to build relationships with community members. And in the fall the police will be joining school personnel for race and equity training, which is designed to help people become culturally competent and knowledgeable of lived experience of others.

My children’s experiences with racism are directly connected to my lived experiences as a black mother. I often fear for their safety.

Four years ago, my son, Brandon Waterman, was engaged in a friendly conversation with two white women, one of them an administrator at the high school, when his supervisor arrived in the car and told them he had received a phone call from a Manchester Public School central administrator (now retired) who happened to be looking out of a window and observed a large black man wearing a summer program staff T-shirt “questioning” and “intimidating” two small white women. I believe if Brandon were white this would not have happened.

I’m sad to say that I could go on.

Unfortunately, it is the reality that some of us—and if not us, our colleagues, our friends, our children’s classmates—must navigate our everyday lives while continuing to cope with discrimination, oppression, and racism.

Even today, even in 2019, even in Manchester, race matters and it will continue to matter for as long as racial bias, discrimination, and institutional racism continue to persist.

For our community to be the best it can be, I believe we need to analyze our beliefs about race, put race at the center and seek to understand and empathize with the lived experiences of people of color. I am proud to say that Manchester is a community that is choosing—through the work in the schools and in the town—to do just that.

A community where everyone’s humanity is acknowledged and respected is a community where race matters. Race matters in Manchester because that it is the sort of community that Manchester is striving to be.

About the author: Rhonda Philbert, the district’s equity coordinator, is also co-chair of the Manchester School Readiness Council, chair of the African American and Black Affairs Council, a member of the Equity and Inclusion Collaborative of Manchester and a member of the NAACP.